River with Rob Mousavi: Gender & Being Iranian-American

TW: transphobia, homophobia, racism, homophobic slurs

Background:

Having sex with someone of the same gender was made a crime punishable by death in Iran in 2013 (Human Dignity Trust). I have never been able to go to Iran, my Dad always said that my Mum needed to go first, as if members of my family hadn’t been going for decades and that my Mum going would change things or prove that Iran wasn’t a ‘dangerous country.’ Once I turned 18 I no longer had to listen to this yet due to the Trump Administration, not the first US regime to attack Iran but making it even more difficult to enter the country, especially with the Muslim Ban, with Iran being on the list of countries. Things may become easier after the recent 2020 US election and my family have continued to travel back to Iran. Iran has the second highest rate of gender reassignment surgery in the world (Bagri), yet I still feel worried about travelling because of my sexuality. Physical safety as a trans person is a growing worry in my mind, having lived most of my life as cis and male I have not had to worry about my personal physical safety, but instead my friends,’ now that worry is directed inwards. The US continues to be incredibly unsafe for transgender people, in particular for Black transwomen, most weeks when I check social media I read or hear of more trans people being murdered. The US does not feel like a safe place to be trans.

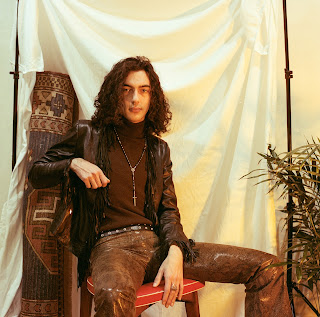

In this photo project I wanted to work with one of my Iranian-American friends, Rob, who like me does not exist on the gender binary and uses they/them pronouns. I’ve known Rob since my first year in NYC and I was incredibly excited to work on this project with them. I looked at this as a way for us to connect over shared identities and explore our experiences, this would be an opportunity for us to help each other and ourselves with navigating these nuances and complexities.

Rob and I sat down to talk before making these photos. Looking back on this evening, it was one of the most natural ways I have photographed someone, we spent around 45min talking before even moving onto the subject of the photos we were about to make. While photographing them I would continue to talk with them about our connections to Iran, what is gender, our relationships to the ideas of womanhood and manhood. Even the concept of a number of genders, it’s all just another box to place people in. Rob spoke more on their thoughts about the term “non-binary”:

“My beef with the word nonbinary is less in the word itself than in its usage and context: it’s used like a third gender and like an identity...I would say it’s more of a dispossesion-because it relinquishes some essential tenet of identity-as well as a reclamation...However, all of this is predicated on Western grammars of liberation and gender understanding… ”nonbinary” to me is a specific practice and ethical position, but one that I acknowledge is not transnational or a perfect solution”

We discussed transitioning and then transitioning “back,” how we should be able to treat our bodies in whatever way we like and that there is no destination. It feels like my body is a vessel in which I experience the world yet I am actively changing it, my body cannot be reduced to one thing. Rob said: “my mind is the vessel and my body is the message.” Transness is not about arriving, there is no conclusion, it’s this idea that we must arrive somewhere for us to be accepted. These labels are still just being used to sort us. I said that I like the term “genderqueer” in a similar way that I use the word “queer” to descripe my sexuality, I don’t want to restrict myself. I said it feels like my body can be a shell, like I should be able to just take it off, that I have no connection to it. What does it mean to be at home in your own body? We talked about ways in which we would change our body. Rob mentioned to me that they remember me saying I hate my body hair, a treat that I (and others) associate with being Iranian, of Middle Eastern heritage. I remember talking about my body hair with them and our friend Ozra, who is also Iranian, how people have always commented on my body hair. We had gone to our favorite Persian restaurant in Manhattan, Ravagh, and talked about the ways in which we and our family view our bodies. How we see family members getting nose jobs, the sadness and pain it brings when I hear other people talking about how excited they are for theirs. In response to Rob, while photographing them, I said that after my recent self portrait series on my relationship with my body and how my tattoos have helped me to feel as if I am claiming my body has helped me immensely with how I feel about my body hair. I told them that it allowed me to feel comfortable taking my shirt off for things besides sex. But regardless of my feeling towards my body hair in the present, I told Rob that with transitioning I will be removing my body hair, or as much of it as I can. I can’t imagine changing my body in the ways that I want to so as to feel more affirmed with my gender without removing my body hair. I said that I wasn’t sure how my being Iranian relates to my gender. In ancient Persia there were supposedly at least three genders, and there have been many artifacts depicting people of the same gender kissing. I asked Rob if they’re out to their family, if they know that they have a boyfriend. Rob responded saying that they don’t like the term ‘coming out,’ saying: “it seems to assimilate to the cishet world, one that is simply an illusion… I’m much more interested in the specificity of my desires than in totalizing sexuality that claims to tell the truth of everything I want.” It feels as if it is belittling us, making it about the people we choose to share this part of ourselves with. We are giving people a gift by sharing, we are saying that we care enough for them to know. It is intimate and not something that can be taken back. They told me their family doesn’t know about their sexuality or their gender. Sharing gender with our Iranian family members also requires another level of complexity because there is no gender in Farsi. Our family members misgender people all the time, consistently using the wrong pronouns to refer to other family members. I told Rob it feels like a joke to me, my family from Iran came to the States a long time ago, and that surely by now they know what they are saying is grammatically incorrect in English. I said that I’m not sure how my family views queer people, it’s not something that gets talked about much, the only conversations I have heard or seen shared between my family members are brief jokes about the word kooni, meaning “faggot” in Farsi. Rob shared an anecdote on their father’s response to hearing CUNY and how he had said it was a “bad word in Farsi.” I grew up with my family, not understanding the concept of ‘extended family,’ my cousins and I sat on Persian rugs eating ghormeh sabzi and rice until we were allowed to sit at the ‘adult table.’ Some of my family know that I am queer but I will not exactly be able to hide transitioning. It will be obvious: I will grow breasts, I will no longer have facial hair, my voice will change, my face shape will change. I cannot hide this part of myself. I told Rob that I plan on telling my parents I’m trans when I go home for winter break and that this time I’m doing it for myself, unlike when I told them I’m queer. I want to start transitioning as soon as I can, this has been something that I have denied about myself since I was eight years old and now that I have finally accepted it, I will not wait any longer. I asked Rob what their connections to being Iranian are and they said they don’t like being nationalistic but still embody their connection to culture. We both agreed that food is such a big part of it. We talked about how race places in with being Iranian. We are both white but we see the microaggressions come out if we talk about our heritage. Rob spoke of how some of their friends back home in Texas don’t think of them as white: “It is interesting how desperate people are for an ‘other’ to the degree that in a group of all white people, whiteness seems to break down into categories… [white-passing] also means there’s a possibility for you to fail… [and] there are different kinds of white-passing, with vastly different stakes… bottom line is I’m white because I benefit from white privilege.” I recounted how when I was in 7th grade I remember two of my classmates saying that the US should have bombed Iran instead of a different country, I told them that “I’m Iranian” and they acted like they didn’t hear even though we were standing a foot away from each other. That in it of itself, is a clear definition of my white privilege while also being Iranian: I have to tell people that I am Iranian for them to treat me differently, I am not perceived as being Middle Eastern. I repeated myself and they continued to ignore me. Rob told me that when Osama Bin Laden was killed, kids in their class had said that their ‘uncle’ had been killed. We talked about how Imperialism is taught at such a young age to American children, that at age 12, kids will discuss bombing a country like America has every right to do so, that they are entitled to do so and should.

Image Exploration:

I chose to photograph Rob in my living room, creating a space for us to safely and comfortably make these images together. I started with the rug rolled up and leaning by the bed sheet backdrop. This rug is not Persian. It was given to me by someone who thought it was and I, like Rob and my family, instantly recognized that it is not. Persian rugs are detailed and use specific colors: often dark reds, deep blues, light cream, often depicting animals and geometric patterns. While my family and I are unable to identify exactly where the rug originates from, I wanted to use it in the images. It acts for us a reminder of the region we originate but also a reminder of our disconnect through living in the states. It is illegal to take Persian rugs into this country, meaning that our rugs are all from our family who brought them over before this ban when they first immigrated. I grew up eating on these rugs, they are what I think of when I think of my family and when I think of home. This rug, while not Persian, still gives me a feeling of familiarity. By propping it against the wall, it acts as a reminder of this disconnect from where our families are from. Rob asked to hold the rug and we continued much of the photo making with them holding it or resting on it. The plant acts as a placeholder for lands that we have not been able to connect with Iran in a physical way but still continue to feel its presence. I chose to use a bedsheet instead of a real seamless and to show the light stands and clamps, our families constructed new lives here while we construct our physical beings. Queerness is a construction of self, it is to acknowledge who we are in all of our forms and in our form, that we are ever changing, ever present, and do not have to arrive at a final form.

Reflection:

This class allowed me to explore intersections and delve into connections between systems in a way no class has previously been able to. For the first time, with the final project, I was given the chance to write and reflect on my gender and ethnicity. Growing up I rarely had opportunities to write about my connection to my culture and heritage and if I did it was often through open-prompt writing, let alone explore my gender. These two things often feel like a battle inside me and telling my family about my gender and sexuality is a consistent worry, one that I need to learn more about where my feelings stem from and how to manage in a healthy way. I do wish we would have had some traditional style lectures, while I very much appreciated the open and conscientious structure of the class, I do find it beneficial for my learning style to still receive the occasional lecture. I find note taking during lectures helps me a lot to comprehend the topics and open forum format for discussion often left it too open. I liked the padlets but thought that padlet itself was not the best format for creating these group dialogue; there are other online websites such as miro that give more freedom in creating and arranging. The group final project has been enjoyable to see my other group members’ work come to life and the way they responded to our collective prompt, especially given the wide range in which our work covered.

Bibliography:

“Iran.” Human Dignity Trust. Accessed November 27, 2020. https://www.humandignitytrust.org/country-profile/iran/

Bagri, Neha Thirani. “In Iran, There's Only One Way to Survive as a Transgender Person.” Quartz. Quartz. Accessed November 28, 2020. https://qz.com/889548/everyone-treated-me-like-a-saint-in-iran-theres-only-one-way-to-survive-as-a-transgender-person/

Comments

Post a Comment